**Marie submitted her story as part of our Overcoming Adversity Contest.**

![]()

by Marie Preston, Monroe, Georgia

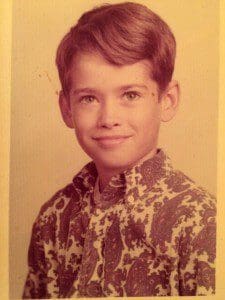

Confronting the horrific death of her 12-year-old brother, she is finding healing and joy.

May 5, 1971 … spring quarter at the University of Georgia on a Wednesday … about 7 p.m. to be exact. As a 20-year-old sophomore, I was at a rehearsal at the Georgia Center with the Opera Ensemble practicing my part as “Princess No. 13” in the musical comedy “Once Upon a Mattress.” I had a serious personal issue to deal with in several days, but it was not something I believed I could share with my parents. I had been taught to handle my own problems and not bring shame to the family. I pushed the issue to the back of my mind. For now not an immediate care in the world did I have…just enjoying the fun of my creativity and the optimism and energy of youth. I had no clue that my false sense of security was about to be shattered.

From the stage I saw one of my Magnolia Manor housemates hurry down the aisle from the back of the theater with an urgent message for me from one of my Monroe, Georgia, neighbors, a Mrs. Manning, who said that my brother Tom had been injured by a gun and had been rushed to Athens General Hospital emergency room. My parents went by ambulance with him, and my housemate offered to take me to the hospital to meet my family. In the car ride, my head started spinning questions of why and how. “We don’t have gun accidents. All of us, including me, were taught how to correctly handle guns.” Imagining the answers opened the panic door as the initial shock set in.

As I ran into the ER, it looked to me as if I had arrived in a surreal, other worldly scene. Across the waiting room I saw my father in his white dress shirt from work covered in blood all over his front and right arm, talking quietly with his brother, John. I did not interrupt but started searching for my mother. I thought it odd that my dad was not with her and my brother. I did not find Mother then but later learned that she was in an isolated room with my brother and a team of doctors. Hospital staff caught up with me, asking who I was. After identifying myself, they directed me to sit in a small, empty room and wait on my parents to come and speak to me as I was told they were with my brother “Patrick.” “Not Tom? “ I asked confusedly. “I had a phone message that it was Tom who was hurt. How did this happen?” I dared to ask. Hospital staff did not say, but slowly, as concerned relatives and close friends of my parents arrived, I learned that Patrick, the youngest of five children, got his 17-year-old brother’s shotgun without permission, took it to the upstairs children’s den area, sat on the sofa, loaded the gun, and it discharged into his lower abdomen. Patrick only lived “the golden hour” after this happened, and there was no way even those triage experienced doctors, some newly returned from seeing the horrors of jungle injuries in Vietnam, could repair his mortal wound.

Patrick died about 8:15 p.m. The coroner wrote that his death was accidental, but as time went on, the truth of the matter was that my 12-year-old brother committed suicide. His shocking act literally and metaphorically “blew” a hole in our family. None of us four surviving siblings was ever the same nor our parents. My dad, a hardened WWII vet, who by grace survived the bloody trenches of France and Germany during 1944-45 and suffered from undiagnosed PTSD the rest of his life, now watched his youngest child die from a violent self-inflicted act. Dad reacted by turning away from what Baptist religion he had and became a humanist. Emotionally, he grew even more wound tightly, drank at night to numb his emotions, and survived a heart attack two years later at the young age of 51. My mother turned fervently toward her Methodist faith practice. She courageously brought a chapter of Compassionate Friends to the community for parents who had lost children. She could speak in the group meetings about that May night in empathy for the losses of others but could not discuss her feelings with us. Mother also renewed her nursing license and went back to practice for another decade and left a scholarship with her earnings to high school seniors in memory of Patrick.

Mom and Dad received counseling individually and had a choice as our parents to emotionally help their surviving children ages 20 (me), 17, 13, and 12 understand the tragedy of what had happened to Patrick. However, their choice was to do nothing. They turned away from us children emotionally. We had no offered counseling. No family group talk EVER in their remaining life on earth to explain what happened. No comforting words or embraces. No opportunity for us children to comfort or embrace them. No counselor at school or at church spoke with us. It was as if this incident was shameful, a negative reflection upon their character and ideals. The “elephant” in the room was to be swept under the carpet. The public persona of our family gave the appearance of being strong and solid, but our family unit was as fragmented as the blast that took our brother’s life.

Over the last four decades since the incident, if brave enough to broach the subject, my brothers and I separately tried to talk to our parents during their remaining years about that terrible May evening and occasionally spoke separately to each other and together as an adult sibling group trying to shed light on how and why this happened. We eventually learned that Patrick had some physical and emotional problems that he did not let us know about. We thought our brother was funny, upbeat and popular. He seemed happy. We saw he had many friends; he was a talented athlete and “B” student. But emotionally Patrick was a broken soul, and life in his pre-teen mind and in his time on “earth school” was difficult. He had deep thoughts about life and his place in it as a member of our family but never told us siblings. He also felt like no one paid enough attention to him and confided this to our grandmother (Mother’s mom) as to how sad and hopeless he felt.

Physically, about a year before he took his own life, he started having fainting spells, with the worst one leaving him unconscious on a concrete floor in a store. Mother took him back and forth to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta trying to find out what was wrong. There was no definitive diagnosis, but Patrick was on medication afterward. However, emotionally he continued to feel sad, angry and rebellious. I thought it was my dad who pushed him over the “emotional cliff” knowing how tough Dad could be on us, but about 15 minutes before he shot himself, Patrick had a “whale” of an argument with my mother when he came in past curfew time after school. Patrick became so angry that he took his own life…the most desperate of acts, forcing what was or was not going on in the dynamics of our family to stop and focus on him. My 12-year-old brother felt he had no hope… no one to help him…no other option. My God…what kind of hell was he in? It was an unbelievable thought. But truth be told, he was not the only Preston in memory to commit suicide. My Grandfather Preston’s youngest brother did the same thing about a decade before Patrick was born.

How does anyone overcome such loss? How does one heal? Certainly my surviving brothers have had their own individual struggles with Patrick’s suicide. Although we are almost 45 years past that numbing evening in May, for me it has been a “circular run of the grief gauntlet” to understand my part in this family tragedy and our learned patterns of behavior. My journey has been full of not wanting to face my emotions. I had to recognize that not dealing with the grief was making me physically sick. I had to recognize my problem, ask for help, seek knowledge, feel the pain and grieve all my losses. I had to forgive myself and my parents. I had to understand that what happened to Patrick was not my fault. I had to accept the choices I made all through my life and make peace with the past. In the words of Wordsworth, I had to “find strength in that which remains behind” in order to move forward and become whole again.

Immediately after Patrick’s death, I was so traumatized that I couldn’t concentrate on my studies and barely finished the quarter. I kept having a recurring dream about Patrick. He would appear to me in a beautiful, green landscape waving from the opposite side of a stream while standing on the edge of a grassy bank. He would tell me he was at peace, and I would always wake up with tears on my face. Initially I tried counseling that I set up for myself, but I couldn’t handle the fog of grief surrounding me. I did not have the courage or energy to do the work. Instead, I became a directionless college dropout. When I did let feelings slip into grief, I felt guilty as the oldest child for not spending more time with Patrick. I kept replaying conversations I’d had with him, searching for clues I had missed.

I didn’t want to go back to school. I found an hourly wage job and briefly moved back home but couldn’t stand living in the house where Patrick took his own life. I ran from the family frying pan into the rebellion fire of a sad, painful, unhealthy, abusive marriage. I sold out for initial attention, excitement, and experience I never had before. I forgot about my self-esteem, my goals, and the quality of life I once wanted for my future. I deceived myself. I gave my heart and youth to someone who presented himself to be what he was not. I wanted safety and security, but after I “woke up” I found myself far from it. I had made a terrible mistake. Every day that I lived with that person I put my physical, emotional, financial and spiritual welfare at risk. I was so ashamed. I was “supposed” to know better. I could not tell my parents how devastated I was. I could not tell my friends about the horrible circumstance I was in. But I carried on as I had seen my parents do…in public, everything was OK, but in reality it was all a facade … my personal hell. I felt so trapped … so stupid … where was my safe harbor?

Still pushing down the grief, I became a workaholic. I created patterns of relentless stress for myself. I did go on to graduate magna cum laude in 1978, and over the course of a 34 year professional career managed to attain additional master’s and specialist degrees. I also reared two children and lived through divorce. I would occasionally get myself back into counseling but never really “let out the ugly” that needed to raise its head. I look back now and find it an absolute wonder and miracle that I survived.

When I retired from my professional career almost four years ago, I finally took time to decompress. What came to the surface were decades of grief that I had not dealt with. I wanted to feel better. By grace I found wonderful spiritual teachers who offered me help. At this writing in my seventh decade, I have begun to finally heal. But I had to understand that THE VERY THING I HAD AVOIDED THE MOST WAS THE THING I MOST NEEDED TO DO. I had to be willing to CHANGE and to bring about that change into my life. I had to show compassion for others…EVEN THOSE WHO HURT ME THE MOST, and I had to learn to FORGIVE MYSELF AND OTHERS. I HAD TO STAND IN MY TRUTH as to what I experienced. Those who have hurt me the most in my life have been my greatest teachers. I have learned to be grateful for my difficult experiences, for in the long view of my life, they have all been blessings. I have learned that we are all victims of victims. My parents, as have I, did the best we knew how to do at the time spent together. But when we know better, we have a choice to do better.

I have embraced the help given me through Louise Hay’s book “You Can Heal Your Life.” Also Dr. Cristiane Northrup’s medical wisdom has pushed me forward by leaps and bounds, especially her discussion of shame and its effects upon the body. I also have found a great resource of teachers through the OWN Network’s “Super Soul Sunday” programs concerning spirituality, forgiveness, courage and recovery. Presentations by Gary Zukav, Michael Beckwith, Tim Story, Iyanla Vanzant, Elizabeth Gilbert, Michael Pollan, and Brene Brown among others have particularly helped me move forward. Reading the autobiographies of people who had difficult circumstances to overcome helped me gain perspective about my own.

I now choose to journal, exercise more, am mindful of my diet, and find comfort in meditation and the creative arts. I use physical therapy, yoga, massage, acupuncture and Reike. I am grateful to sit in the company of and be instructed by Caroline Brown through her “Heal Your Life” Seminar and receive her gifts at Sharing Love and Light (sharingloveandlight.com); Melissa Wells, Vanessa Platt and Dr. Cheryl Larson have used their skills to help me; Dr. Rita Dickinson gave me the contact for Dr. Mitzi Crall whose wisdom and talent first “put a name on my pain” and who gently led me through “A Journey of Hope” therapy program for victims of sexual trauma and sexual betrayal; Don Simmons gave me “spot on” advice by encouraging me to contact Georgia author Lauretta Hannon whose wit, writer’s workshop, and generous encouragement made my heart sing!

I now choose joy. I have the courage and energy to do the work to heal. It is my greatest wish that writing about my path to overcoming adversity helps others. How many counselors does it take to change a light bulb? Only one if the light bulb wants to be changed.